Industrialist and philanthropist Samuel Courtauld played a distinctive role in shaping the United Kingdom’s appreciation for Impressionism, significantly transforming its perception and acquisition during a period when Great Britain was still languishing in its conservative past. His innate inclination towards discretion and a reserved demeanour may explain why he remains a relatively obscure figure today. Nevertheless, the collection he curated during the 1920s comprised some of the most iconic masterpieces of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, making them indispensable in recounting the narratives of these pivotal artistic movements.

The Courtauld family’s lineage can be traced back to Huguenots who, in their escape from religious persecution in France during the late 17th century, found sanctuary in the city of London. Initially renowned for their mastery in the art of crafting exquisite silverware, the family underwent a remarkable transformation in the late 18th century, shifting their focus towards the intricate craft of silk weaving. Their fortunes burgeoned, ultimately reaching unprecedented heights in the early 20th century when they pioneered a groundbreaking synthetic fibre known as ‘artificial silk,’ or viscose. This innovative breakthrough propelled their enterprise to monumental proportions, positioning them as one of the globe’s foremost textile manufacturers.

In the year 1921, the same year that Samuel Courtauld assumed the role of chairman at Courtaulds Ltd, the company embarked upon its most remarkable phase of expansion. This momentous growth not only elevated the company’s standing but also provided Samuel Courtauld with the resources and influence to ardently pursue his intrinsic passion for the collection of art.

Samuel Courtauld’s strong commitment to public service, deeply rooted in his religious heritage and nurtured by his parents, Sydney and Sarah, was instilled in him early in his childhood by his family. His parents actively participated in local politics and served on school and hospital boards. Nevertheless, as his sister aptly pointed out, ‘his independent taste was his own’ and his appreciation for modern art developed from personal predilection.

Samuel Courtauld’s initial encounters with the world of art were a mixed experience. His early visits to the National Gallery seemed somewhat reluctant, with him expressing disapproval of what he described as “all these brown old things.” However, his enthusiasm for Old Masters blossomed during his travels in Italy after his marriage in 1901 to Elizabeth, with whom their relationship was nourished by shared interests and tastes in music, art, books, and even in people. The great galleries of Florence and Rome played a pivotal role in this transformation. Samuel recalled that ‘the Old Masters had come alive to me, and the British academic art had lost its appeal. In the former, I now perceived a remarkable mastery infused with profound emotion and vitality.’ These very qualities that captured his imagination in the work of the Old Masters later became evident in the Impressionists’ creations, convincing him that French modern art was not a subversion of tradition but a rejuvenation of ‘the potent and thrilling undercurrents still coursing beneath the surface of the paint’ in the finest Old Masters’ works.

This pivotal artistic enlightenment abroad, as well as his exposure to two significant exhibitions in London shortly after, sparked his lifelong taste for French modern painting. The first artistic illumination was the group of paintings from the collection of the late Sir Hugh Lane, held in 1917, which included eight important impressionist paintings such as Manet’s Music in the Tuileries Gardens and Renoir’s The Umbrellas, constituting a ‘real eye-opener’ for Courtauld.

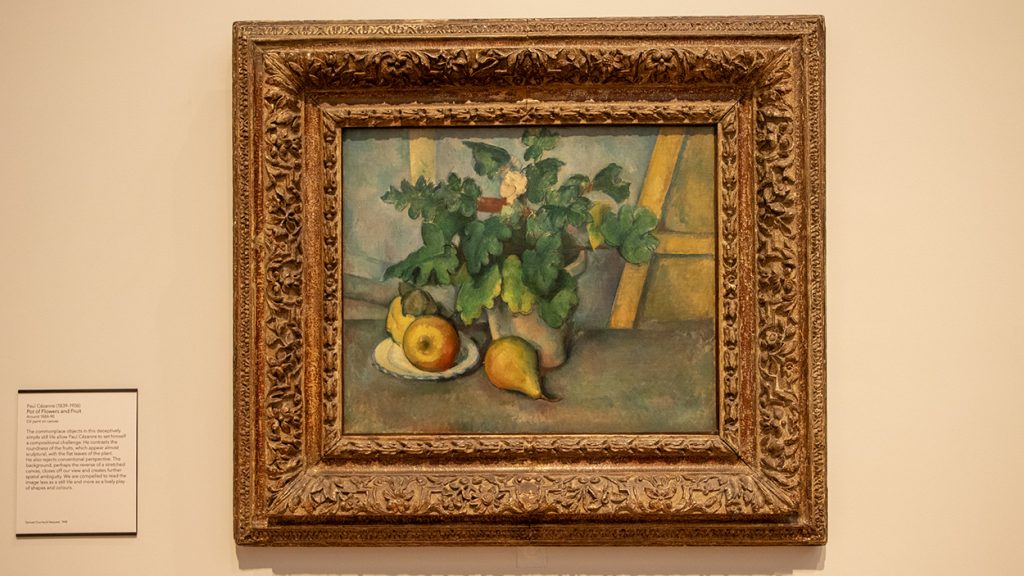

A few years later, in 1922, Pictures, Drawings, and Sculpture of the French School of the Last 100 Years was shown at a private club on Savile Row. Courtauld recalled walking around the exhibition with a friend and stopping in front of a Cézanne: ‘a young friend who was a painter of conventional portraits…led me up to Cezanne’s Provençal Landscape…. though genuinely moved he was not very lucid, and he finished by saying…“it makes you go this way, and that way, and then off the deep-end altogether!” At that moment, I felt the magic, and I have felt it in Cézanne’s work ever since.” Both exhibitions, besides kindling Courtauld’s passion for Impressionism, must have also conveyed to him the joys of collecting and the influence that private individuals could wield in shaping the broader artistic preferences.

It is remarkable to realise that the collection was still in its early stages when Courtauld shifted his focus from private to public collecting. In June 1923, he corresponded with the Director of the Tate Gallery, expressing his belief that ‘the Modern Continental Art movement deserves better representation in the National Collection.’ To support this cause, he generously offered a substantial sum of fifty thousand pounds. He suggested the establishment of an acquisition committee, which he would chair, with the specific mission of procuring paintings that exemplified the modern art movement.

This bold and visionary initiative, along with Courtauld’s subsequent service as a benefactor and trustee of the Tate Gallery and the National Gallery, played a pivotal role in overcoming the hesitancy and conservatism prevailing within the British art establishment. The Trust’s acquisitions were insightful and included works by Manet, Renoir, Seurat, Degas and Van Gogh. Initially displayed at the Tate, the paintings were transferred to the National Gallery during the 1950s and 1960s once their status as modern artworks was no longer relevant.

The Courtauld Gallery’s semi-circular staircase, now adorned with freshly painted Prussian blue bannisters, serves as the intriguing entry point for visitors embarking on a challenging and intellectually stimulating journey through centuries of artistry, thoughtfully distributed across three meticulously organised floors. Following a two-year hiatus for renovations, the gallery has reopened its doors with grandeur, attracting both its dedicated patrons and new enthusiasts to its streamlined and immaculate spaces.

Before renovation works commenced in 2018, both the gallery and the affiliated Courtauld Institute, a world-famous college for the study of the history and the conservation of art, found their home within the north wing of Somerset House in London, a grand architectural masterpiece crafted more than two hundred years ago by the renowned architect William Chambers for King George III. This structure, designed with meticulous facades that conceal intricate interiors, was purpose-built to accommodate various government offices and learned societies.

This towering architectural staircase, with its majestic sweeping incline, has also been the source of much amusement, as evidenced by an 1811 caricature by the satirical artist Thomas Rowlandson, titled The Stare Case. This whimsical work is now accompanied by an informative label in the Courtauld’s revitalised space. In this caricature, a group of fancifully clad visitors tries in vain to ascend to the gallery’s third floor, historically home to the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. What catches their attention, however, is not the artful nudity of the marble Venus discreetly nestled in a nearby niche, but rather the accidental exposure of a lady who has stumbled most disgracefully on the stairs.

This playful, yet rather misogynistic image fosters a titillating interplay, cleverly echoed in its irreverent title, between the physical and cultural ascent represented by the staircase and the moral descent facilitated by the power of the human gaze. Visitors of both past and present find themselves entangled in the complex dynamics of art, humour, and human curiosity within the Courtauld Gallery’s newly invigorated setting.

The climb up the staircase offers more than just a humorous and biased critique of unruly visitors. Sir William Chambers had a grander vision in mind. He aimed to provide visitors with the opportunity to transition ‘from darkness to light’ on a symbolic journey to Enlightenment. This transformation turns the displayed objects into symbols of the ever-evolving human intellect, culminating on the third floor.

Throughout its history, the gallery has approached this narrative and its symbolism with a historical perspective, recognising them as significant yet somewhat outdated relics of the past. Nevertheless, the architectural principles guiding the gallery’s design continue to hold sway in the present-day itinerary through its permanent collection.

The recently revamped Middle Ages galleries, now relocated to the first floor, present a remarkable showcase of objects displaying exceptional craftsmanship; the metalwork objects from the Islamic world shine under intimate, low lighting, and a gathering of Italian Renaissance tin-glazed pottery, with its pearlised iridescent surfaces, glimmers within the atmospheric room. As I ascend to the second floor, the journey from darkness to light becomes explicit. The space broadens to reveal the Blavatnik Fine Rooms, adorned with elaborate decor and featuring 14th-18th century artworks arranged around grand fireplaces.

Finally, the steepest flight of stairs leads visitors to the third floor, housing the 19th-20th century permanent collection and the new temporary exhibition spaces, culminating in the modern and spacious LVMH Great Room. This room is divided by white low walls and bathed in natural light streaming in from a large glass opening in the ceiling, marking one of the most substantial changes after the building renovations. The third floor undoubtedly showcases the Gallery’s most cherished masterpieces.

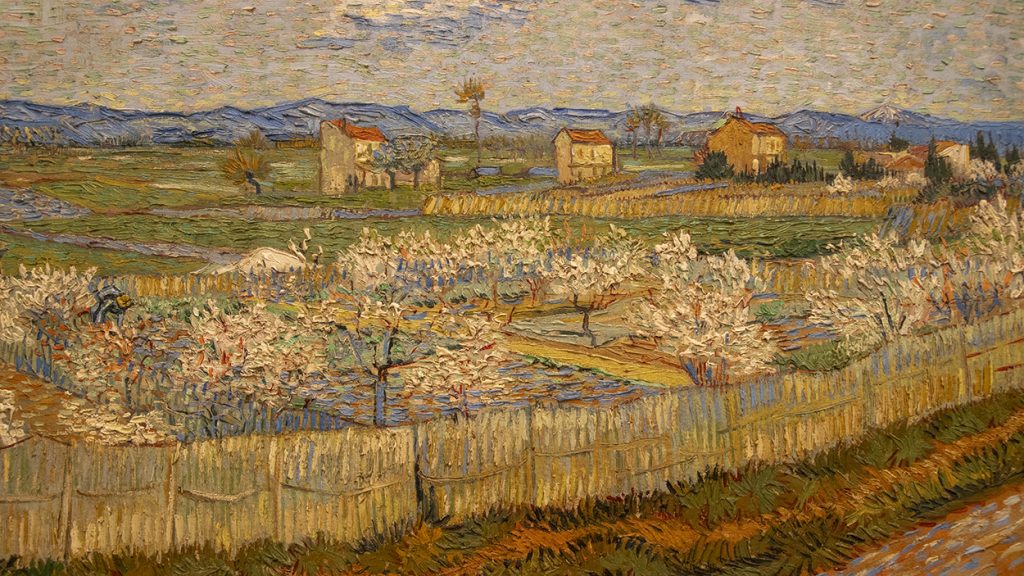

The lit-from-within vivacity and saturated colour palette of the French Impressionists has always fascinated me. Their harmonious, slightly off-kilter colour compositions and lyrical brushstrokes seem to pull at an emotional response rather than the need for any deep academic dissection. Wonderfully tactile in quality, the surface of Degas’s After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, 1895-1900, purchased by Courtauld in 1927, is mesmerising. Its lavish pastel hatching in warm coral-orange tonality together with the evident markings from the charcoal creates an intensely textural finish and is reminiscent of a handloomed Oriental carpet; enticing me to caress its coarsened surface. Though drawn to Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, for its immediate familiarity and its powerful handling of colour and brushwork that rightly declares the artist’s ambition as a master painter, my eye wanders to the left, to one of his more naturalistic paintings Peach Trees in Blossom, 1889.

Executed shortly after his series of haunting self-portraits, this work exhibits his renewed commitment to working with nature. The predominately cool palette of blues and greens illuminate the canvas, depicting a bright, clear agricultural landscape with highlights of ruddy earth tones evoking the rich, fertile soil and the terracotta roof tiles on the farmhouses, fashioned from that same reddened earth. It is a scene that seems immortal, quietly undisturbed by the world of modern art and the hastening Industrial Revolution that is happening during this same period. The delicate whisps of white used for the fleeting peach blossoms and the extraordinary variety of brushstrokes seem at once calming and alive. Van Gogh’s painting had its own evocative effect on Samuel Courtauld, who, in 1935, wrote to his friend Lady Aberconway: ‘the journey through Kent was lovely: the bright green grass, and blossoming fruit trees, and the newly washed sky, and water glistening everywhere reminded me of the Van Gogh landscape at Portman Square’ (Courtauld’s residence at the time).

Samuel Courtauld held the belief that one’s emotional reaction to a piece of art held far greater significance, satisfaction, and enduring value when compared to any intellectual or scholarly approach. According to his close friend, the novelist and playwright Charles Morgan, discussing painting with Samuel Courtauld was engaging in conversations that transcended the realm of art itself. Courtauld perceived art as being inherently democratic, offering its substantial rewards to everyone without requiring extensive academic knowledge but rather relying on essential, universally applicable – though demanding – qualities: ‘unfettered imagination, human emotion and spiritual aspiration go to the creation of all great works, and a share of the same qualities is needed for the reading of them’. While Samuel Courtauld’s personal writings are regrettably absent, Morgan succinctly summarised his viewpoint in the following manner:

‘To think, in a vaguely philanthropic way, that it is useful to make great pictures to the public is one thing, but Sam Courtauld’s thought on this subject was another… he is by no means to be thought of as disembarrassing himself of great possessions. His idea was clear, positive and passionate. It was this: That human imagination… has a tendency to stagnate; that this stagnation, or freezing up, is a kind of spiritual death in men, in classes, and in nations; that art in all its forms has a power to renew our imaginative life, but that this power is effective in us only if we are capable of yielding to it, and do not, in ignorance or fashion or prejudice, harden our hearts… Therefore he established the Courtauld Institute , enabled opera and chamber music, and gave his pictures – I will not say ‘to the Nation’ but rather to each man or woman or child who, coming upon one of those pictures by chance, might be prompted, not only to admire or praise or enjoy it as a thing observed, but to receive it inwardly, to be pierced by its arrow, to discover in its life a renewal or unfreezing of life’s imaginative stream. His desire was not to make connoisseurs of the public but that each of us should transmute Cezanne or Manet or Renoir into the poetry of his or her private life.’

Some information gathered for this article was obtained from my reading of the exceptional book The Courtauld Collection: A Vision for Impressionism from the 2019 exhibition of the same name, held at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, France.

Such an interesting article Rose. I had never really known of the man although I had heard of the Courtauld Gallery. What an exceptional person he was to see the beauty and potential in those Impressionist painters. Beautifully written and photographed as usual!