The atmosphere that engulfed Great Britain during the Victorian era was one laden with monumental new discoveries; it was a revolutionary time of new cutting-edge technologies and extensive scientific exploration of the natural world. The British Empire, which during its height in 1922 reigned over more than a quarter of the Earth’s land surface, began to spread its rule and power throughout the world. This period of colonisation brought power and wealth to Britain, funding exciting new inventions, technologies, and the trade of exotic goods. These far-flung commodities, brought back to Britain from abroad by English businessmen and wealthy scholars, were revered by the aristocratic Victorians as symbols of power and status.

In 1687, a British physician and naturalist, Sir Hans Sloane, embarked on an exploration of Jamaica, as well as the West Indies, as a personal physician to the 2nd duke of Albermarle, Christopher Monck, who had been appointed to govern the island. The journey to Jamaica provided Sloane with the chance to pursue his interest in the natural sciences, and during the 15 months of his travels, he visited multiple islands where he collected over 800 plant species. He also recorded information on and collected specimens of various fish, mollusks, and insects, as well as his observations of the local peoples and contemplations of the natural phenomena of the area. His resultant studies and the specimens he collected during the voyage laid the foundation for his later contributions to botany and zoology and for his role in the formation of what would later become the British Museum.

Sloane was also known as an avid collector, and he benefited greatly from the acquisition of the cabinets of other collectors, including amateur scientists and botanists. When Sloane retired from active work in 1741, his library and cabinet of curiosities had grown to be of unique value, and on his death, he bequeathed his collection to the nation, on condition that Parliament pay his executors £20,000. The bequest was accepted and went to form the collection opened to the public as the British Museum in 1759.

One of the grand Victorian museums of the 19th century, the Natural History Museum owes its inception and much of its unique naturalistic design to Sir Richard Owen, a leading comparative anatomist, botanist and palaeontologist who became the first superintendent of the British Museum’s natural history collection. Unhappy with the lack of space for its ever-growing collection of natural specimens, Owen convinced the British Museum’s board of trustees that a separate building was needed to house these national treasures. In 1864 Francis Fowke, the architect who designed the Royal Albert Hall and parts of the Victoria and Albert Museum, won a competition to design the Natural History Museum. However, when Fowke unexpectedly died a year later, the role passed to the relatively unknown architect Alfred Waterhouse.

Although the building’s design reflects Waterhouse’s style and character as an architect, it is also a testament to Owen’s original vision of what the museum should represent. In the mid-nineteenth century, museums were expensive places visited only by the wealthy few, but Owen insisted the Natural History Museum should be free and accessible to all. He was adamant that the structure be grand enough to house and display all the new discoveries and artefacts in what he referred to as a ‘cathedral to nature’.

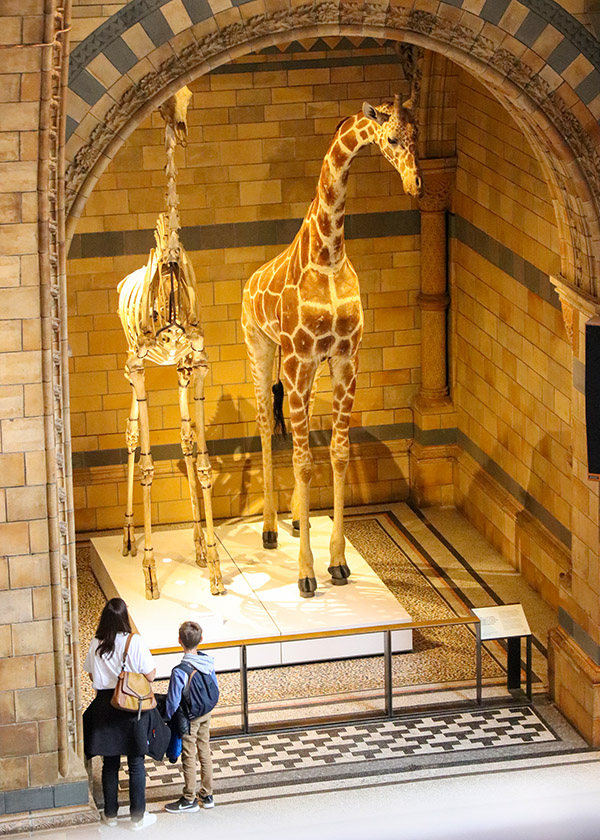

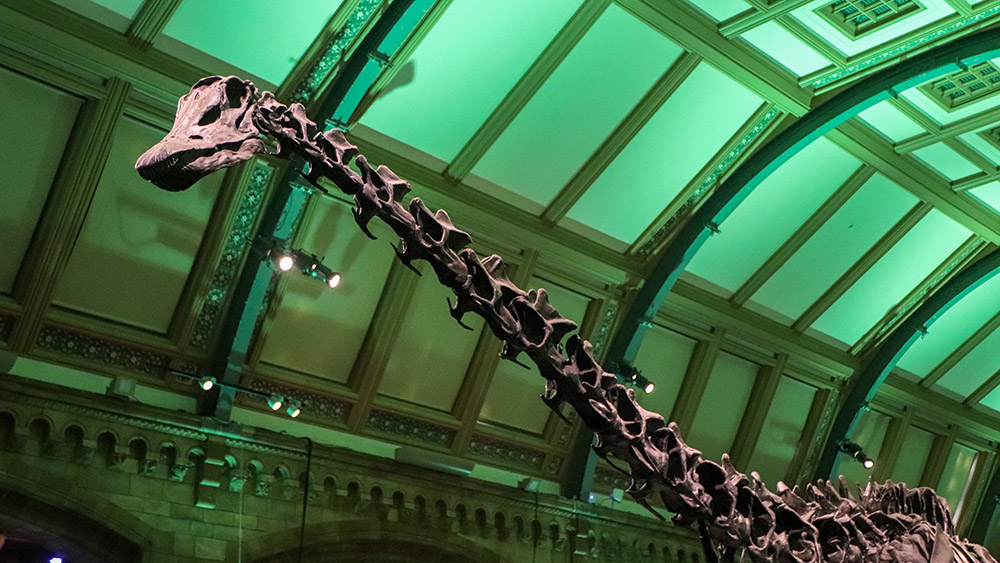

Owen’s foresight has allowed the Museum to display very large creatures such as whales, elephants, and dinosaurs, including the beloved Diplodocus cast, affectionately known as Dippy, that has been on display at the Museum for over a hundred years. Although the structure of the museum was undertaken to adequately and safely display the ever-growing collection of specimens, it was also integral to Owen that the building was created as a homage to the natural world and to showcase its importance to the general public.

He demanded that the Museum be decorated with ornaments inspired by natural history, and this set the tone for Waterhouse who also designed an incredible series of animal and plant ornaments, statues, and relief carvings throughout the entire building, including the exterior. The architect used fawn and blue-grey coloured terracotta for the entire building as the inexpensive and durable material was both resistant to acids and washable, ideal for use in facing buildings in dirty Victorian cities. The result is one of Britain’s most striking examples of Romanesque style architecture, which is considered a work of art in its own right and has become one of London’s most iconic landmarks.

During a past trip to Oxford, that idyllic university town huddled amongst the bucolic countryside just west of London, we visited the town’s own Museum of Natural History, established in 1860 to consolidate scientific studies from across the University of Oxford. Though much smaller than London’s Natural History Museum, the collection is quite incredible, and the building itself was also designed to incorporate the imagery of the natural world into its structure. The experience was one I will never forget, and as exquisite as the exhibits were, it was the building and its intricate details that really captured my eye.

The train journey from our home in west London to the buzzing area of South Kensington is a relatively easy affair. Only a short half hour trip, including a brisk walk on our end and an exit from South Kensington station that practically plonks us at the museum door. The area around South Kensington on a weekend is a hive of activity, and families with strings of kids in tow are out in force enjoying the best the area has to offer. In this city block alone you will find the Natural History Museum, the Victorian and Albert Museum, and the Science Museum, and a short stroll will take you up to Kensington Gardens, Hyde Park, and Kensington Palace, and if you enjoy a spot of exercise, you can even take a walk over to marvel at the golden gates of Buckingham Palace.

With so much intellectual splendour on our doorstep it is near impossible to live in London without making the short pilgrimage to the museum district to revel in a little bit of cultural enrichment. For me, South Kensington and its surrounding streets are a testament to the architectural magnificence and elegant charm that this city is so famous for. Luxuriously wide tree-lined streets slice through the city with precision town-planning creating a smorgasbord of architectural delights, each grand old structure more splendid than the last. Many times, we have passed by the awe-inspiring façade of the Natural History Museum on our way to somewhere else, stopping to admire the beauty of her monumentality before scurrying off to our destination for the day.

As we ascend from the dimly lit enclave of the South Kensington underground train station, we emerge bleary eyed into the full assault of daylight. With a quick internal thank you to whoever placed the station so conveniently close to the museum we follow the already swelling crowd towards the blaringly obvious building to our right. On a crisp golden September morning, amongst a consort of fellow visitors, we snake our way towards the elegant projecting central entrance, flanked either side by two imposing towers which surround a highly decorative recessed arched portal. The building is a vision of beauty, and the cathedral-like entryway with its arched glass windows and Romanesque symmetry draw the visitor forward, not to worship at the house of God, but to marvel at the wonder and magnificence of the natural world.

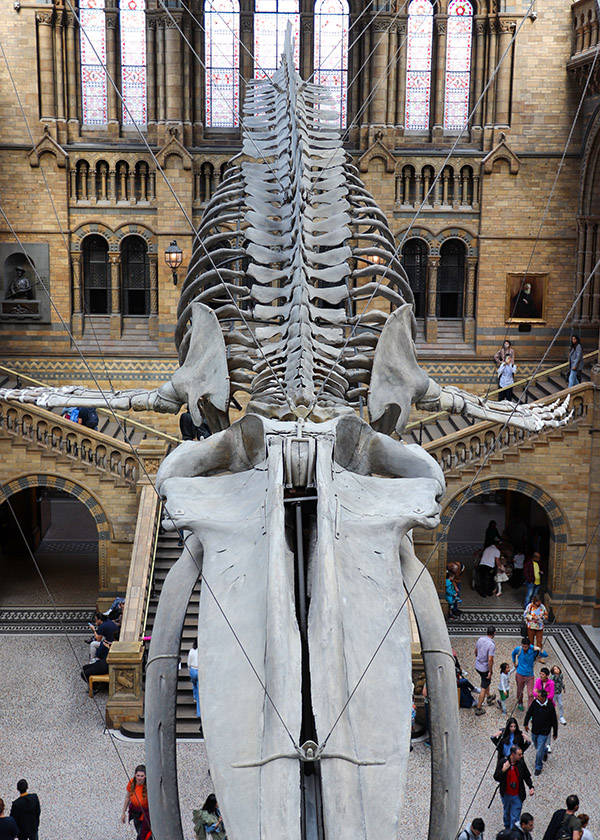

For most, the lure of the exhibits and the spectacle of the dinosaurs is the drawcard. Yet, although these feats of nature are no doubt miraculous, it is the building and its exquisite details that I find so utterly mesmerising. Once inside, most visitors will notice the colossal Blue Whale that hangs suspended from the ceiling in diving position before anything else. Its enormous jawbone and curving spine are too wondrous to ignore. The whale’s skeleton is real, not cast as many of the larger specimens are, such as Dippy the Diplodocus dinosaur, whose equally impressive skeleton was cast from the remains of five different Diplodocus discoveries. Rather than dwarf the space the 4.5 tonne Blue Whale skeleton only reiterates the monumental scale of the building and seems like the perfect prelude to the magnificence to come. The sight is a constant reminder of the importance of ecological conservation.

With much wonder to distract the eye it would be understandably easy to miss the astonishing details of the structure itself. Look for a moment through the skeleton’s structure and you will notice the 162 ornately decorated panels, bathed in golden light and illustrated by hand, dating from when the Museum opened to the public in 1881. The botanical illustrations, lavished with shimmering touches of silver and gold, perfectly showcase the planets abundance of plants. If you take the time to absorb the glorious artistic details you will spot fruit trees such as lemons and pears, drugs such as tobacco and opium poppies, and garden ornamentals such as rhododendrons, irises, and sunflowers. The panels show plants of all varieties, in a style that evokes the Arts and Crafts movement of the Victorian era.

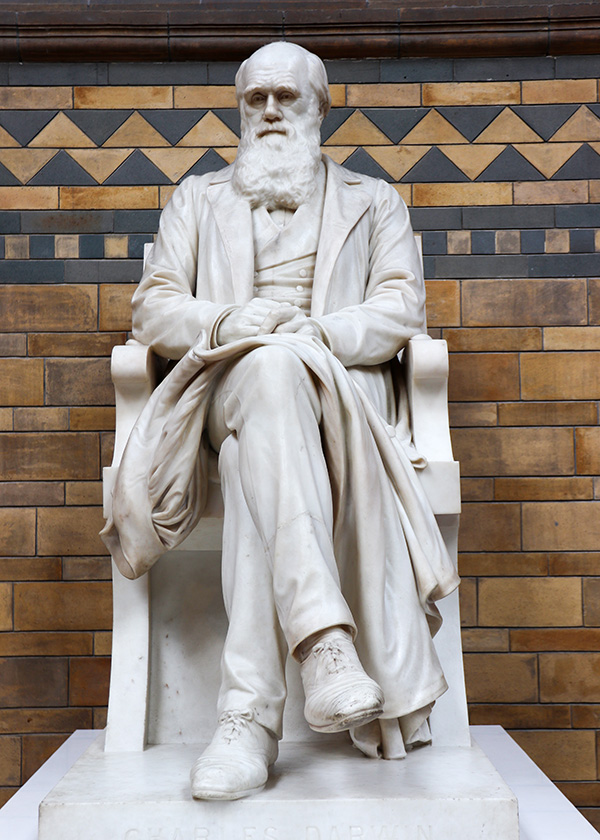

Native English plants are depicted alongside exotic species such as cacao and Banksia, an Australian shrub named after Sir Joseph Banks, the English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences who made his name after he took part in Captain Cook’s famous voyage to Australia and New Zealand in 1768, and whose statue also sits overlooking Hintze Hall.

As we continue our exploration of the museum, it is the building that remains my primary focus, and it is a joy to notice even the tiniest details of the fish and shells that have been meticulously carved into the pale terracotta brickwork. The Natural History Museum and its contents are a breathtaking site and one of the greatest collaborations between humankind and the natural world. To wander through the halls is a journey back through millions of years of history and discovery, and an absolutely marvellous lesson in attentiveness.

Oh Rose, thankyou for taking me with your eyes!

P x

My pleasure Pippa! What a visual treat it was!

Rose x

Rose, thank you for showcasing the Natural Museum which I visited honks ago. I always find all the exhibits overwhelming especially the sizes of them. And I agree totally I like the architectural beauty of the building with carved animals and vertebrates, and most of all the botanical panels. As always, very informative.e

Thank you Sandie! What a fascinating place! Everywhere I turned the details delighted and surprised.

Rose x

What a site for a natural history museum. Wonderful !

I love how the building is a beautiful homage to the specimens housed within. Incredible!

Rose x