Disappointment looms large in life, and although not always catastrophically so, my tulip dreams this past week were nevertheless, monumentally shattered. But alas, we pick ourselves up in times of crisis, put our big girl pants on, and soldier onwards as best we can with heads held high and spirits triumphantly roused. Such calamitous events last weekend – a rather heavy downpour – caused the unfortunate transformation of the grounds of the Moreton Hall Gardens Tulip Festival into a soggy, Glastonbury-esq mess. Swirls of jewel-coloured tulips, their frilly petals unfurling before my very eyes, had been whirling through my mind for weeks, and I was eager – desperate – after an unrelenting and particularly long winter for a riotous carnival of scent and colour. I was hungry – downright ravenous – for spring in all its spectacular, tulip-y glory!

After a momentary inner tantrum, and a few good minutes of revelling in my own flowerless despair, I grabbed our hefty National Trust guidebook, put on a pot of coffee, rummaged around in the kitchen cupboards for something decidedly chocolatey to eat, and set to work finding a replacement destination for our newly freed bank holiday affair. With my easy-going, pragmatic husband by my side, and the mollifying trace of cocoa in my mouth, I began to see that not all floriferous hope was altogether lost. Travellers and expats don’t venture to London for the ominous weather, we come for the seemingly infinite number of wonderous things to see and do. If, by some unyielding will of the weather gods your event is unfortunately cancelled, no matter, there are a myriad of equally glorious wonders to fill your exploratory days.

Lulled by chocolate and the promise of adventure, I sat patiently while Dan rattled off places within driving distance of our west London home. My only stipulations for our choosing, I insisted, was the promise of a surrounding cottage garden and an onsite café where one could partake in something quintessentially English to eat and drink. We settled upon Ightham Mote, an astounding Tudor manor house – believed to be England’s oldest Medieval home – in the north-west corner of the county of Kent, a little more than an hour’s drive from central London.

Although the previous day – and the cause of my great flowery discontent – had seen resolute torrential rains, today the magic of spring was palpable in the early morning breeze that filtered through our living room window, bringing with it traces of blossom and a hint of the warmth that was to come. With all thoughts of tulips and rain-sogged festivals a mere memory, we set off in search of our rental car – which despite its gaff-taped side mirror and constant dashboard warning that the bonnet was open (when indeed it wasn’t) – proved to be a trusty and reliable metallic-blue steed for the day’s adventure that lay ahead.

The few photographs that peppered the crammed pages of our National Trust guidebook revealed a picturesque old stone and wood-beamed manor house, surrounded by a languid body of water and a series of storybook arched bridges connecting the building to the wider landscape beyond. With an established enveloping garden, and an adjacent café nestled conveniently at the entryway to the property, the encompassing moat – a mystical feature I had only ever seen in movies and read about in history books – seemed like the icing on an already sugary cake!

After a white knuckled drive through the chaotic streets of London, out along the homogenous connecting highway, and culminating in a series of narrow, winding country lanes, we park our trusty metallic-blue steed and scramble desperately towards the scent of brewing coffee. Predictability can often be dull and rather tedious, as Eleanor Roosevelt famously said, “If life were predictable it would cease to be life and be without flavor.”. Yet I can think of nothing more deliciously predictable and mouth-wateringly welcome than a fresh-from-the-oven buttery scone heaving with lashings of clotted cream and the delectable flavours of homemade berry jam – made from those very berries that grow wild amongst the hedgerows that line the perilously narrow, winding country lanes.

Bellies full of clotted cream, we are more than grateful for the downward incline towards the grand old, moated house. I catch glimpses of the building through the foliaged framing of the looming pine trees, and for the first time since we decided upon our visit, I grasp just how incredibly ancient and majestic the property really is. If it wasn’t for the occasional visitor walking by, clad in their modern-day weekend wear, I would feel I’d lost all sense of common time and place.

Burnished with dew, the outstretched lawn – left to naturalise and grow long like the unkempt hair of a fresh-faced, young hippy – is studded with early spring wildflowers in varying shades of yellow and pink. A choral of darling birdsong fills the air like an enchanted fairy-tale and I half expect Snow White – her lips as red as roses and her skin as white as snow – to sashay around the corner, her cascade of jet black hair carried delicately by a flutter of obedient, red-breasted robins.

A harmonious mishmash of Medieval architecture, built from Kentish ragstone and great Wealden oaks, the house sits poised upon its restful perch amidst the protective waters of the surrounding moat. The original builder, although unknown, was clearly someone of wealth. Contrary to most moated buildings constructed during the Middle Ages, Ightham Mote was not conceived in its watery position merely for fortification purposes. The house, much smaller at the time of its original construction in the early 1300’s, was built upon a series of streams and lakes fed by the nearby natural springs that run through the encompassing property.

What is now the site of the South Lake, previously there would have stood a mill pre-dating the house, yet subsequent owners reconstructed the landscape, and transformed the working-mill into a pleasure ground where one could host guests and stroll the lake shores enjoying the local birdlife and the unfurling of the changing seasons.

The core of the house dates from the 1340s, yet a series of complex alterations and additions were made in the late 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. Although Ightham Mote bears few external signs of change in architectural style – partly due to the modest ambitions of its successive owners, who expanded the house only as their needs dictated, and in sympathy to the building’s Medieval origins – the interiors have undergone centuries of renovation in accordance with the changing fashions. Yet for all the conversions that it has seen, Ightham Mote somehow manages to create a harmonious whole, as contrasting architectural styles blend seamlessly as you float from one room to the next.

Entering the grand house through its ancient, time-worn wooden door, underneath the imposing Gate Tower, just as Medieval knights must have done more than 700 years before us, feels rather surreal at first – suddenly I have a notion of being rather under-dressed. The inner courtyard, with its patchwork of honey-coloured stone pavers worn down by centuries of daily wear, is an inward sanctuary, sheltered from the frigid winter winds and trapping the welcome sunshine within its thick, absorbing walls. Originally, water would have been collected from the central stone well, providing the household and its inhabitants with plenty of fresh aqua from the pulsating stream below. Now resplendent in a cascade of flowering spring bulbs, the well presides over the courtyard, a glorious reminder of the estate’s humble beginnings. Today, the courtyard gathers a smattering of sensible-shoed visitors, eyes turned upward in unified wonderment at the majesty of their surrounds. However, during its heyday this enclosed space must have been a cacophony of bustling daily life, where maids plunged rope-tied wooden buckets deep into the recess of the well, and guests were greeted ceremoniously by those deemed worthy enough to be put in charge.

The interiors of Ightham Mote are a hodgepodge of styles, yet The Grand Hall at the building’s entryway – the home’s oldest room – is classically Medieval, with fanciful carvings of musicians and performers adorning the walls, this was once a place of feasting and celebration. Passing through the dimly lit room, I am aware of the intense reflection filtering in from the still waters below, casting illuminating shards of light into forgotten corners of the room. I stand here, silent within this ancient room, wondering if Caravaggio were here, would he apply his deft hand to paint this atmospheric space, with its chiaroscuro so perfectly and harmoniously in place. Heading towards the spectacular Jacobean staircase, I sense the watchful gaze of past ancestors, whose portraits were eerily immortalised many centuries ago.

Passing through the darkened halls, I pause at one of the Gothic leaded windows to admire the placid steel-grey water below – distorted into gentle ripples by the thickened handmade glass. From the ground level outside, upon entering the property and first witnessing the monumental house, the enveloping moat seems quintessentially Medieval England nestled snuggly in its hidden Wealden valley. Yet, from up high, as I gaze down towards the surrounding moat, I feel a surreal twinge of that otherworldliness that washes over me during trips I’ve taken to Venice in the not-so-distant past. That slightly unnerving sensation when faced with water at your ground floor seems a tad bizarre no matter where on earth you are.

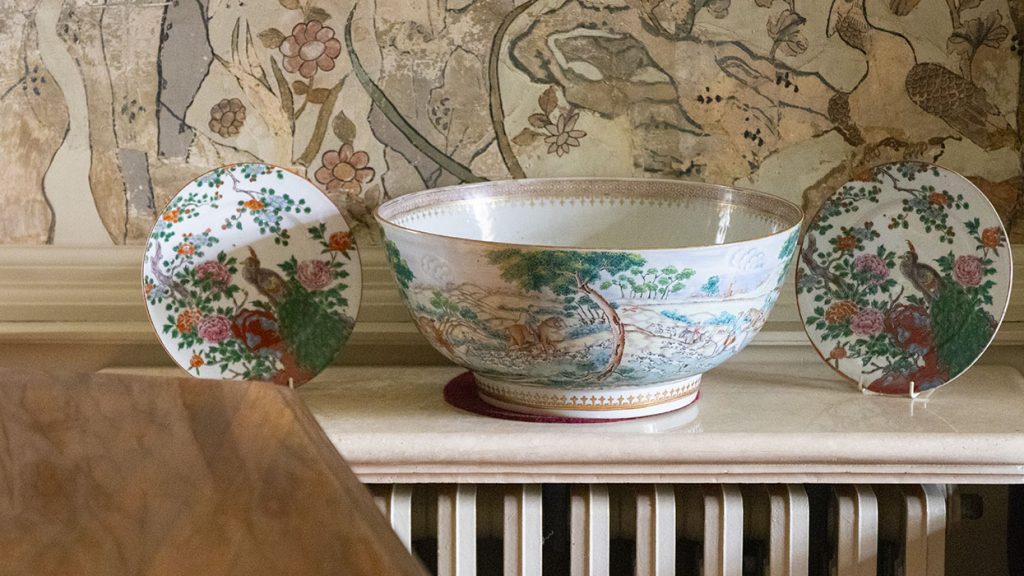

The Medieval austerity fades as I enter The Drawing Room. My spirits, already riding high on a rush of textural delights, are catapulted to dizzying heights when faced with the glorious hand painted 18th century Chinese wallpaper that cocoons this gloriously decadent room. So wonderfully rich and painterly, with its swirling floral motifs and exotic oriental birds, I want to wrap myself up within its heavenly embrace and wear it like a sumptuous brocade coat. What a sensational treat! Jewel-coloured magnolias – as big as a human head -burst into flower on thick and twisting branches, whose outstretched arms are adorned with a menagerie of woodland birds and ripening pomegranates.

The vivid brushstrokes, now worn and crumbling due to time’s indiscriminate force, were presumably once rich in depth of colour and hue. Cobalt blue and white porcelainware punctuate the space, their bulbous forms and slender necks painted in floral ornamentation are a vibrant contrast to the worn and faded grandeur of the antique papered walls.

Enveloped in this wondrous space, brimming with gilded accents, and sweeping views out across the wider Kentish landscape beyond, I could rest for hours – were I allowed. A card table has been placed by the fireplace, bordered by four Baroque-style, faded red and cream upholstered chairs. I begin to fantasise how one might elegantly splay their fan of cards, triumphantly revealing a winning royal flush, while casually sipping one’s sloe gin from an immaculately polished crystal glass.

Oh my goodness Rose such an incredible place to see! I still can’t get over how a building from over 700 years is still intact – such history to experience.

What a beautiful place, so beautifully described. Thank you Rose – it’s on our visit list now!

That wallpaper is amazing!